Radon–Nikodym theorem

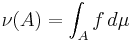

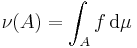

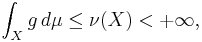

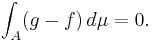

In mathematics, the Radon–Nikodym theorem is a result in measure theory that states that, given a measurable space (X,Σ), if a σ-finite measure ν on (X,Σ) is absolutely continuous with respect to a σ-finite measure μ on (X,Σ), then there is a measurable function f on X and taking values in [0,∞), such that

for any measurable set A.

The theorem is named after Johann Radon, who proved the theorem for the special case where the underlying space is RN in 1913, and for Otto Nikodym who proved the general case in 1930.[1] In 1936 Hans Freudenthal further generalized the Radon–Nikodym theorem by proving the Freudenthal spectral theorem, a result in Riesz space theory, which contains the Radon–Nikodym theorem as a special case. [2]

If Y is a Banach space and the generalization of the Radon–Nikodym theorem also holds for functions with values in Y (mutatis mutandis), then Y is said to have the Radon–Nikodym property. All Hilbert spaces have the Radon–Nikodym property.

Contents |

Radon–Nikodym derivative

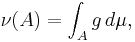

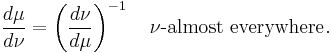

The function f satisfying the above equality is uniquely defined up to a μ-null set, that is, if g is another function which satisfies the same property, then f = g μ-almost everywhere. f is commonly written dν/dμ and is called the Radon–Nikodym derivative. The choice of notation and the name of the function reflects the fact that the function is analogous to a derivative in calculus in the sense that it describes the rate of change of density of one measure with respect to another (the way the Jacobian determinant is used in multivariable integration). A similar theorem can be proven for signed and complex measures: namely, that if μ is a nonnegative σ-finite measure, and ν is a finite-valued signed or complex measure such that  , there is μ-integrable real- or complex-valued function g on X such that

, there is μ-integrable real- or complex-valued function g on X such that

for any measurable set A.

Applications

The theorem is very important in extending the ideas of probability theory from probability masses and probability densities defined over real numbers to probability measures defined over arbitrary sets. It tells if and how it is possible to change from one probability measure to another. Specifically, the probability density function of a random variable is the Radon–Nikodym derivative of the induced measure with respect to some base measure (usually the Lebesgue measure for continuous random variables).

For example, it can be used to prove the existence of conditional expectation for probability measures. The latter itself is a key concept in probability theory, as conditional probability is just a special case of it.

Amongst other fields, financial mathematics uses the theorem extensively. Such changes of probability measure are the cornerstone of the rational pricing of derivative securities and are used for converting actual probabilities into those of the risk neutral probabilities.

Properties

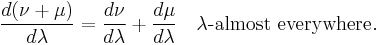

- Let ν, μ, and λ be σ-finite measures on the same measure space. If ν ≪ λ and μ ≪ λ (ν and μ are absolutely continuous in respect to λ), then

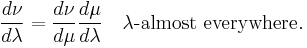

- If ν ≪ μ ≪ λ, then

- In particular, if μ ≪ ν and ν ≪ μ, then

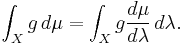

- If μ ≪ λ and g is a μ-integrable function, then

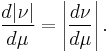

- If ν is a finite signed or complex measure, then

Further applications

Information divergences

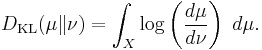

If μ and ν are measures over X, and ν ≪ μ

- The Kullback–Leibler divergence from μ to ν is defined to be

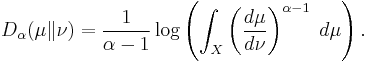

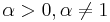

- For

the Rényi divergence of order α from μ to ν is defined to be

the Rényi divergence of order α from μ to ν is defined to be

The assumption of σ-finiteness

The Radon–Nikodym theorem makes the assumption that the measure μ with respect to which one computes the rate of change of ν is sigma-finite. Here is an example when μ is not sigma-finite and the Radon–Nikodym theorem fails to hold.

Consider the Borel sigma-algebra on the real line. Let the counting measure, μ, of a Borel set A be defined as the number of elements of A if A is finite, and +∞ otherwise. One can check that μ is indeed a measure. It is not sigma-finite, as not every Borel set is at most a countable union of finite sets. Let ν be the usual Lebesgue measure on this Borel algebra. Then, ν is absolutely continuous with respect to μ, since for a set A one has μ(A) = 0 only if A is the empty set, and then ν(A) is also zero.

Assume that the Radon–Nikodym theorem holds, that is, for some measurable function f one has

for all Borel sets. Taking A to be a singleton set, A = {a}, and using the above equality, one finds

for all real numbers a. This implies that the function f, and therefore the Lebesgue measure ν, is zero, which is a contradiction.

Proof

This section gives a measure-theoretic proof of the theorem. There is also a functional-analytic proof, using Hilbert space methods, that was first given by von Neumann.

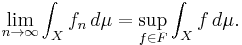

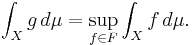

For finite measures μ and ν, the idea is to consider functions f with f dμ ≤ dν. The supremum of all such functions, along with the monotone convergence theorem, then furnishes the Radon–Nikodym derivative. The fact that the remaining part of μ is singular with respect to ν follows from a technical fact about finite measures. Once the result is established for finite measures, extending to σ-finite, signed, and complex measures can be done naturally. The details are given below.

For finite measures

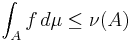

First, suppose that μ and ν are both finite-valued nonnegative measures. Let F be the set of those measurable functions f : X → [0, +∞] satisfying

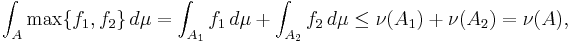

for every A ∈ Σ (this set is not empty, for it contains at least the zero function). Let f1, f2 ∈ F; let A be an arbitrary measurable set, A1 = {x ∈ A | f1(x) > f2(x)}, and A2 = {x ∈ A | f2(x) ≥ f1(x)}. Then one has

and therefore, max{f1, f2} ∈ F.

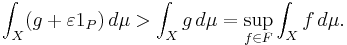

Now, let {fn}n be a sequence of functions in F such that

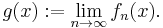

By replacing fn with the maximum of the first n functions, one can assume that the sequence {fn} is increasing. Let g be a function defined as

By Lebesgue's monotone convergence theorem, one has

for each A ∈ Σ, and hence, g ∈ F. Also, by the construction of g,

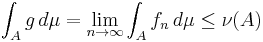

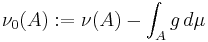

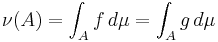

Now, since g ∈ F,

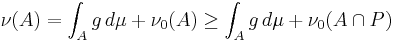

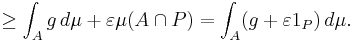

defines a nonnegative measure on Σ. Suppose ν0 ≠ 0; then, since μ is finite, there is an ε > 0 such that ν0(X) > ε μ(X). Let (P, N) be a Hahn decomposition for the signed measure ν0 − ε μ. Note that for every A ∈ Σ one has ν0(A ∩ P) ≥ ε μ(A ∩ P), and hence,

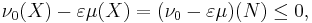

Also, note that μ(P) > 0; for if μ(P) = 0, then (since ν is absolutely continuous in relation to μ) ν0(P) ≤ ν(P) = 0, so ν0(P) = 0 and

contradicting the fact that ν0(X) > ε μ(X).

Then, since

g + ε 1P ∈ F and satisfies

This is impossible, therefore, the initial assumption that ν0 ≠ 0 must be false. So ν0 = 0, as desired.

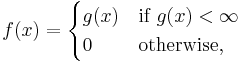

Now, since g is μ-integrable, the set {x ∈ X | g(x) = +∞} is μ-null. Therefore, if a f is defined as

then f has the desired properties.

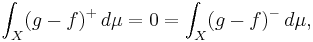

As for the uniqueness, let f, g : X → [0, +∞) be measurable functions satisfying

for every measurable set A. Then, g − f is μ-integrable, and

In particular, for A = {x∈X | f(x) > g(x)}, or {x ∈ X | f(x) < g(x)}. It follows that

and so, that (g−f)+ = 0 μ-almost everywhere; the same is true for (g − f)−, and thus, f = g μ-almost everywhere, as desired.

For σ-finite positive measures

If μ and ν are σ-finite, then X can be written as the union of a sequence {Bn}n of disjoint sets in Σ, each of which has finite measure under both μ and ν. For each n, there is a Σ-measurable function fn : Bn → [0, +∞) such that

for each Σ-measurable subset A of Bn. The union f of those functions is then the required function.

As for the uniqueness, since each of the fn is μ-almost everywhere unique, then so is f.

For signed and complex measures

If ν is a σ-finite signed measure, then it can be Hahn–Jordan decomposed as ν = ν+−ν− where one of the measures is finite. Applying the previous result to those two measures, one obtains two functions, g, h : X → [0, +∞), satisfying the Radon–Nikodym theorem for ν+ and ν− respectively, at least one of which is μ-integrable (i.e., its integral with respect to μ is finite). It is clear then that f = g − h satisfies the required properties, including uniqueness, since both g and h are unique up to μ-almost everywhere equality.

If ν is a complex measure, it can be decomposed as ν = ν1 + iν2, where both ν1 and ν2 are finite-valued signed measures. Applying the above argument, one obtains two functions, g, h : X → [0, +∞), satisfying the required properties for ν1 and ν2, respectively. Clearly, f = g + i h is the required function.

Notes

- ^ Nikodym, O. (1930). "Sur une généralisation des intégrales de M. J. Radon" (in French). Fundamenta Mathematicae 15: 131–179. JFM 56.0922.02. http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm15/fm15114.pdf. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ^ Zaanen, Adriaan C. (1996), Introduction to Operator Theory in Riesz spaces, Springer, ISBN 3-540-61989-5

References

- Shilov, G. E., and Gurevich, B. L., 1978. Integral, Measure, and Derivative: A Unified Approach, Richard A. Silverman, trans. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486635198.

This article incorporates material from Radon–Nikodym theorem on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.